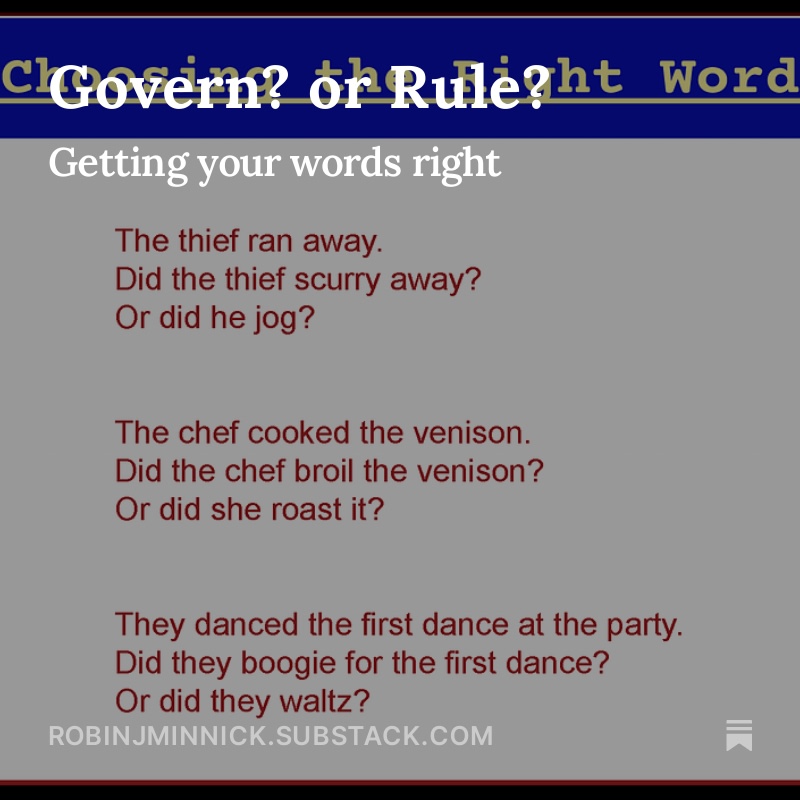

…a little piece on the importance of word choice

Tag Archives: #betterwriting

Comments on consistency

[excerpted from my current post on “Do You Know Where YOUR Story Is?]

- I don’t care if all the inhabitants of a planet are legless, have a single blue eye, gills, and live in a tank where they are dependent on water, melons, and cress to live. Just don’t suddenly have their out-of-town cousin travel in on the next train walking on three legs, smoking a cigar, and using four eyes to watch me out of the back of their head. It doesn’t fit the world you built.

- Writing romance? I know, love at first sight. But meeting a mysterious stranger, marrying them on the same page and going off to live in Saigon when you’re a celibate rocket scientist in the midst of a critical development is not going to work. That scientist, upon the entrance of the stranger, would more logically say, “Get out of my lab, I’m busy. Security!” If that romance is going to happen, it won’t be the way the writer wrote it the first time.

- Time travel; it’s tricky. There are various types of time travel, and you have to decide what rules yours is going to follow. Does the traveler control the travel? Do they remember their own time? Can they get back? And the all-important: will anything they do in the past affect the future they left behind? Whatever rules you choose, you have to work consistently within them or readers will call foul. I certainly will.

- Just as bad—not playing fair with the reader in a mystery. Mystery lovers want to solve the mystery along with the detective. Not letting them have the same clues the detective does isn’t fair. It’s fine if the detective doesn’t reveal what they’ve concluded from the clues—after all, you want that big reveal at the end. But you can’t hide the actual clues from the reader. (Although you can make them obscure.)

I’ve probably driven writers crazy harping on this, but it bears repeating.

No matter how unique, exotic, bizarre the world a writer creates becomes, it needs to maintain an internal consistency. Even if that world is based on being random and illogical. Then it must be consistently inconsistent.

–moi

Sometimes maintaining order in our fictional worlds is all we can maintain. Do so.

A Plethora of INKAS

Note: For those who are serious about being published–whether by yourself or a traditional publisher–there’s a helpful and practical site out there that specializes in articles about material pertinent to the process. Started by professional book marketer Dave Chesson, Kindlepreneur (https://kindlepreneur.com) provides technical information on publishing in basic terms that writers new to the process can understand. Today’s post draws some of its specific information from one of his own articles about the difference between a novel and a novella. For more information on that particular subject and what it can mean, click on this link, https://kindlepreneur.com/novel-vs-novella/ .

Now, about those INKAS…

Today’s INKA formats emphasize the qualities of longer forms of writing versus shorter. There’s a lot of categories characterized by their length. But the actual word count isn’t the only difference. Manuscript length–or word count– definitely affects the total product in particular ways. Fewer words mean you can’t tell as much. It also means every word must do as much work as possible. It’s one reason many writers find short stories — of any kind — more difficult than longer ones.

You can divide all writing into categories of Long and Short. There’s novels, novellas, and novelettes. There’s long stories and short stories. There’s vignettes and flash fiction. In non-fiction that is written as a narrative–such as memoir or human-interest pieces are, there are categories that differentiate by length as well. So where does the length affect come into play? As noted above, you obviously can’t tell as much with fewer words. Therefore, your writing must be tight. Words must be precise, conveying meaning without excessive adverbs or even adjectives.

Now, about those INKAS…

Today’s INKA formats emphasize the qualities of longer forms of writing versus shorter. There’s a lot of categories characterized by their length. But the actual word count isn’t the only difference. Manuscript length–or word count– definitely affects the total product in particular ways. Fewer words mean you can’t tell as much. It also means every word must do as much work as possible. It’s one reason many writers find short stories — of any kind — more difficult than longer ones.

You can divide all writing into categories of Long and Short. There’s novels, novellas, and novelettes. There’s long stories and short stories. There’s vignettes and flash fiction. In non-fiction that is written as a narrative–such as memoir or human-interest pieces are, there are categories that differentiate by length as well. So where does the length affect come into play? As noted above, you obviously can’t tell as much with fewer words. Therefore, your writing must be tight. Words must be precise, conveying meaning without excessive adverbs or even adjectives. Making A word count shortens the STORY word count.

—————————————————————–

Making A word count shortens the STORY word count.

——————————————————————————

Making each word count means you can tell more in your story. Not just in plot either. You can develop characters more fully and even handle multiple character plotlines in less space.

We’ll use novel and novella as examples of long versus short.

Think of a novel as a leisurely stroll through a well-appointed park dotted with nooks and crannies and playgrounds and places for things like chess and bocce or horseshoes. Maybe you meet a neighbor and have a short chat or start a prolonged discussion with a new friend. Then you go home and work out whether or not you want to join that political group your friend has invited you to, and you call them later in the evening to decline, wondering what ever possessed you to consider it in the first place. That’s a lot of physical and emotional territory for a simple walk, and it can have a lot of emotional complexity.

Novella, a shorter style, is more like a brief walk to the mall where you and a friend do some shopping, eat at the food court and maybe throw coins in the mall’s fountain while you discuss how to fix your respective romantic issues. An enjoyable outing, but faster-paced, covering less territory, and over quicker than the outing described above.

How does all this come into play when you are writing?

I’ve seen writers who spent talent and words creating an extensive novel on the events of one day. I’ve also seen writers who tried to encompass multiple lives and decades in a long story, which is even shorter than a novelette (which in turn is shorter than a novella). Whether you do it before you write a single word or when you begin your revisions, you need to choose an appropriate length for what you are trying to accomplish with your writing. Consider these questions.

- How (and for how long) do you want to hold your readers’ attention?

- How many characters’ stories do you need to include to make your point, whether it be to inform or to entertain?

- How enmeshed in your characters and their world do you want your audience to be?

- Does your writing style tend toward flowing words and conversational tone? Or is it more to-the-point and informative?

- What will your publishing media be? Digital or hard-copy magazine? Self- or traditionally published book? Web content?

All of these are contributing factors to what length you choose to write to.

And then there’s the day when you simply sit down with a good idea and begin to write, not knowing exactly where the story is going or how long it will be, but it’s a story you feel you must write.

There is one important thing to remember. Write your story whatever length it takes to tell it completely. Writers often begin a short story only to find out it needs to be a novel, or it grows into one all on its own. Occasionally they write a novel that can’t be supported by its content; it needs to be a long story or a novella. So, write it out as long as it takes. When you’re finished, if you really want the length to be something different, then it is up to you as the writer to revise/edit the piece to fit your needs, still keeping the essence of what you were trying to say.

The table below summarizes INKAs for various lengths of writing. I began writing INKAS when I worked with young students, and the INKAS were based on the requirements of a city-wide writing contest. Because new writers come in all shapes and sizes, I’ve kept the elements in INKAS pretty basic. Unfortunately, that makes for repetition, but it also means you can spot the similarities and differences quickly.